Personal Statement and Portfolio

Adhvai Deepak Menon

Design · Computation · Biological Systems

Design and Artificial Intelligence @ SUTD

"I learn by designing and making.

Software is my studio. Biology is my material. Code is my craft."

At SUTD, I want to develop as a designer who thinks in systems.

I want to learn how ideas move from iteration to prototype to impact,

surrounded by people who believe that making is understanding.

adhvai.com

My Journey

From Observation to Design

The Earliest Fascination

Biology first appeared to me as something I could see and feel. The earliest memory I have of being fascinated by living things was watching lines of ants at my grandfather's house in Hyderabad. They came in different sizes and behaved in coordinated ways without anyone instructing them. I didn't have the language for biology yet, but I understood that life had structure.

Patterns Everywhere

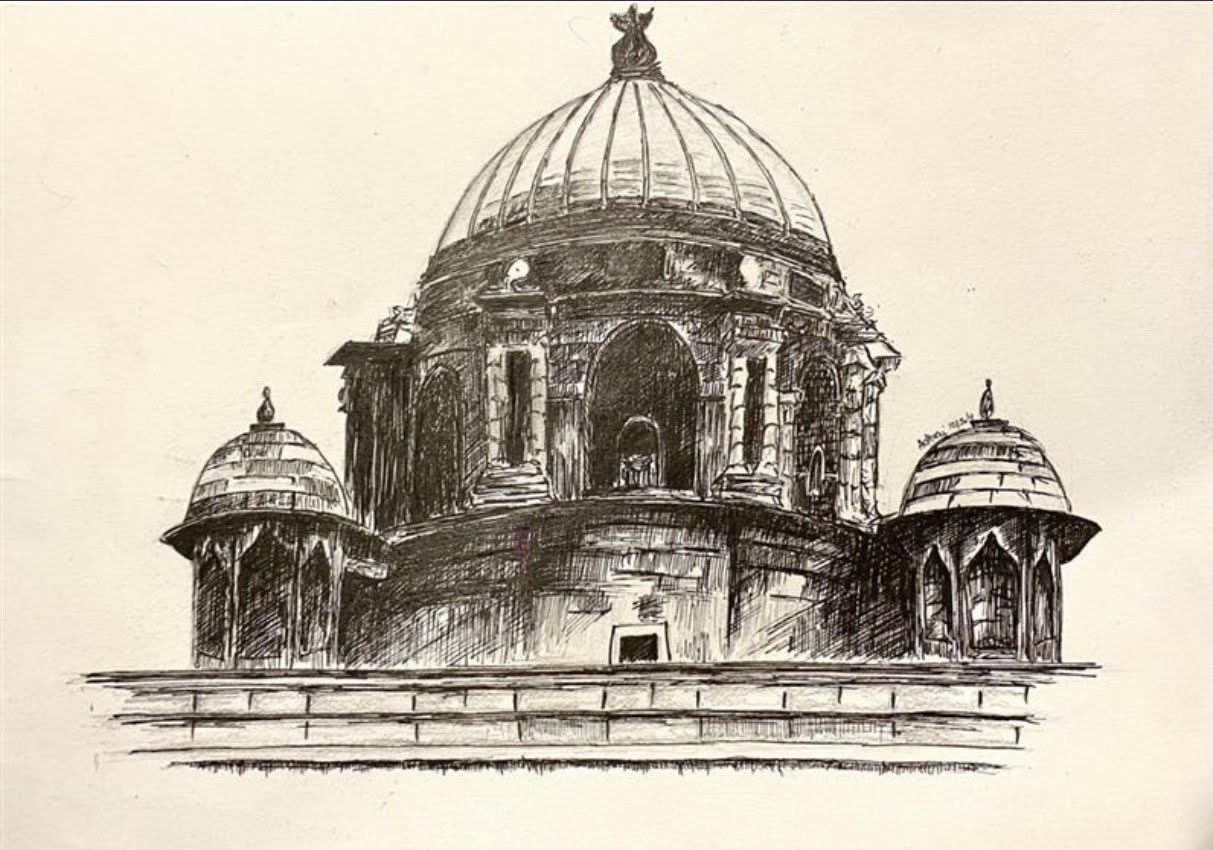

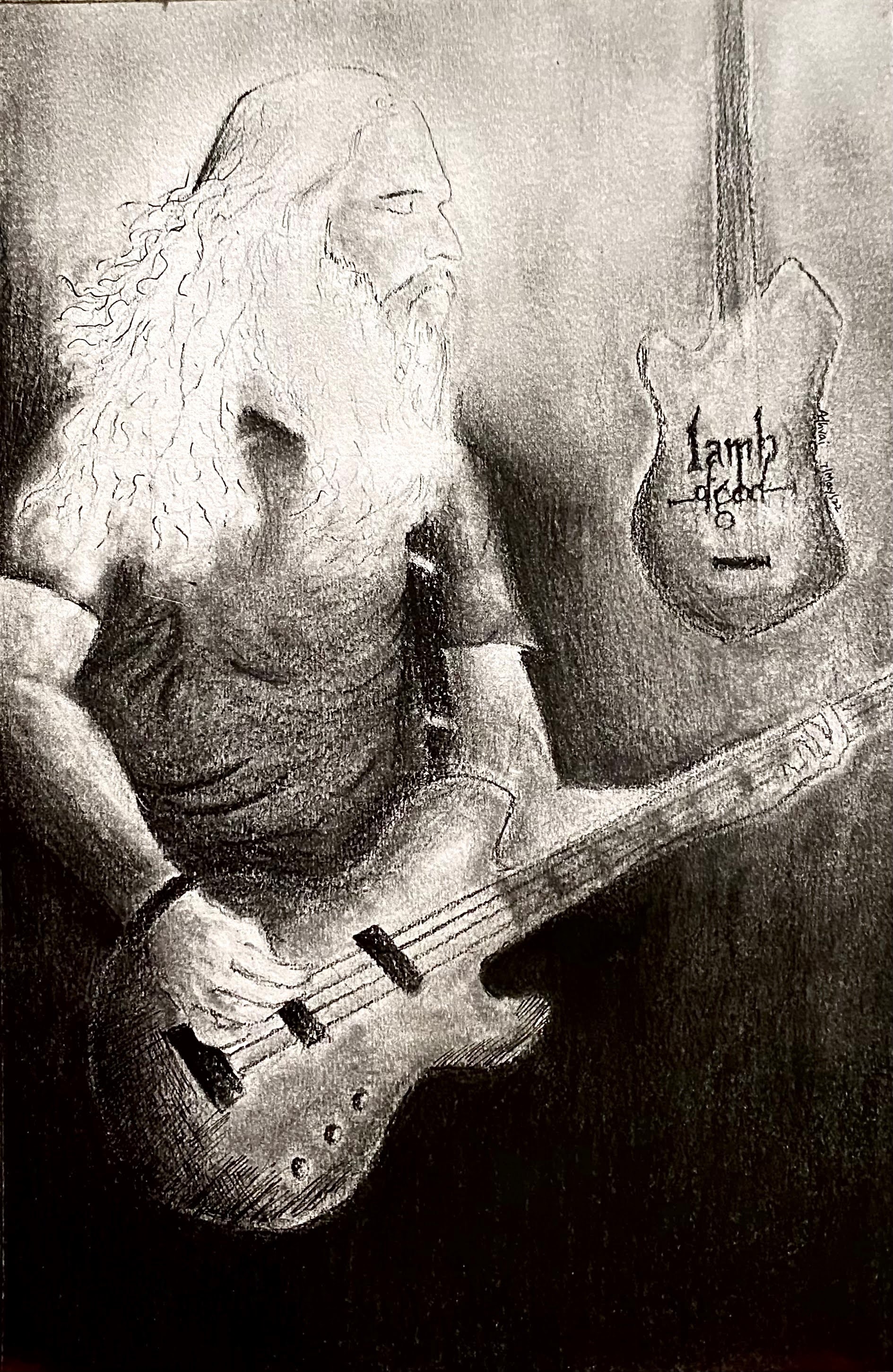

That instinct continued when I began sketching. I drew people, objects, and repeating natural patterns. Drawing made me pay attention to how things were built and how form related to function. Later, cooking pulled me even deeper. Eggs turning from liquid to solid under heat, dough rising, dosa batter fermenting. Cooking felt like watching chemistry and biology happening on a plate.

This attention to form has shaped how I live. I own fewer clothes, but they're designed. I notice when something is made with intention, whether it's a chair, a typeface, or how a kitchen is organized. Good design isn't decoration to me. It's evidence that someone cared about how something works.

The Moment It Clicked

The moment it became intellectual rather than sensory was when I read The Gene by Siddhartha Mukherjee. It opened up the idea that life isn't just what we see, but information encoded, transmitted, mutated, and expressed. I remember pausing at the chapter about how a single mutation could ripple upward into visible traits and disease. It was the first time I saw biology as both history and engineering.

A New Mental Model

Instead of treating it as memorization, I began thinking of DNA as information, amino acids as components, and mutations as changes in a system. This made me curious about the kind of biology that links to engineering and computation rather than medicine.

"I learn best by making. Software became my studio, and building became a way of understanding."

Why I Build

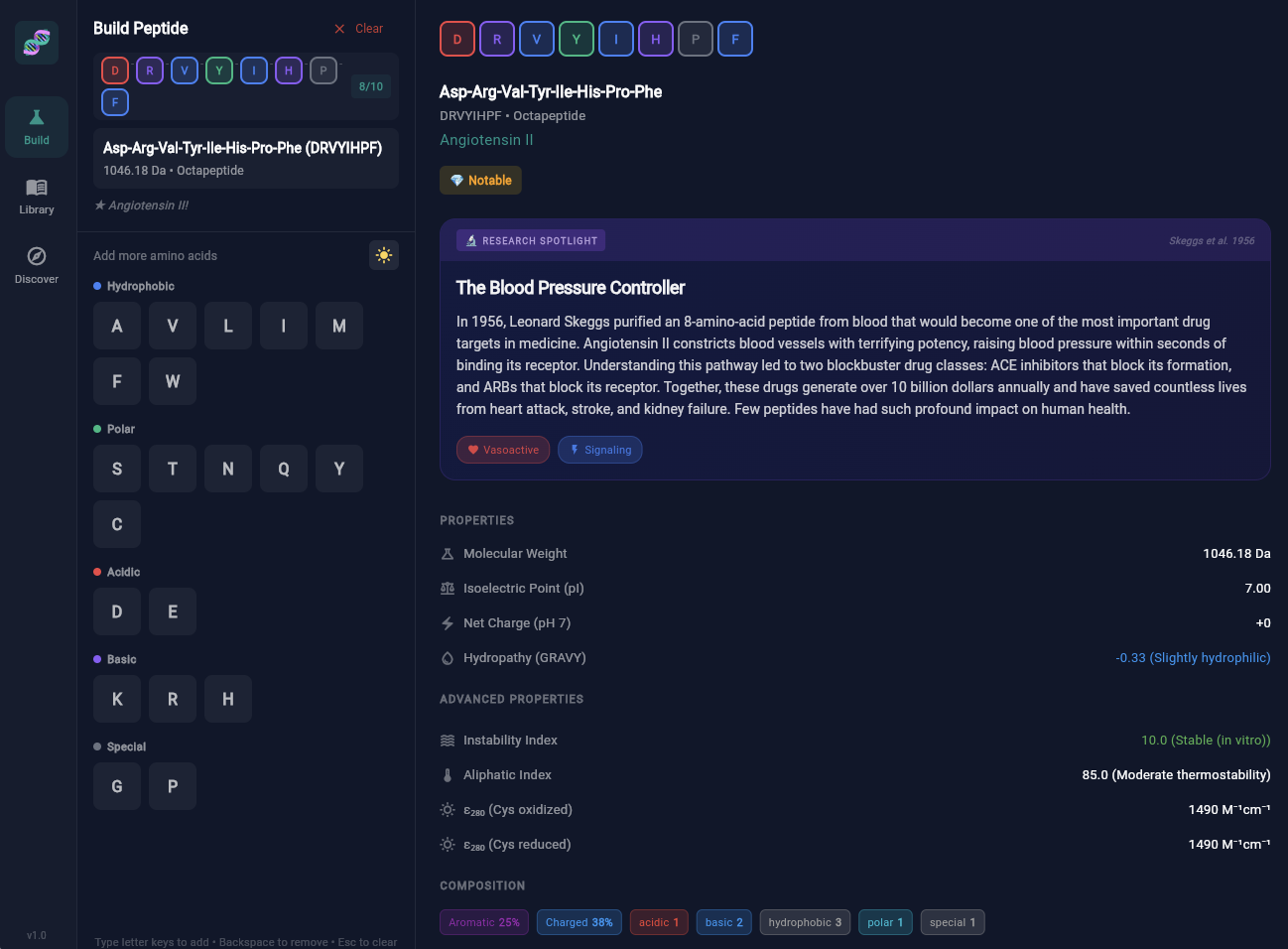

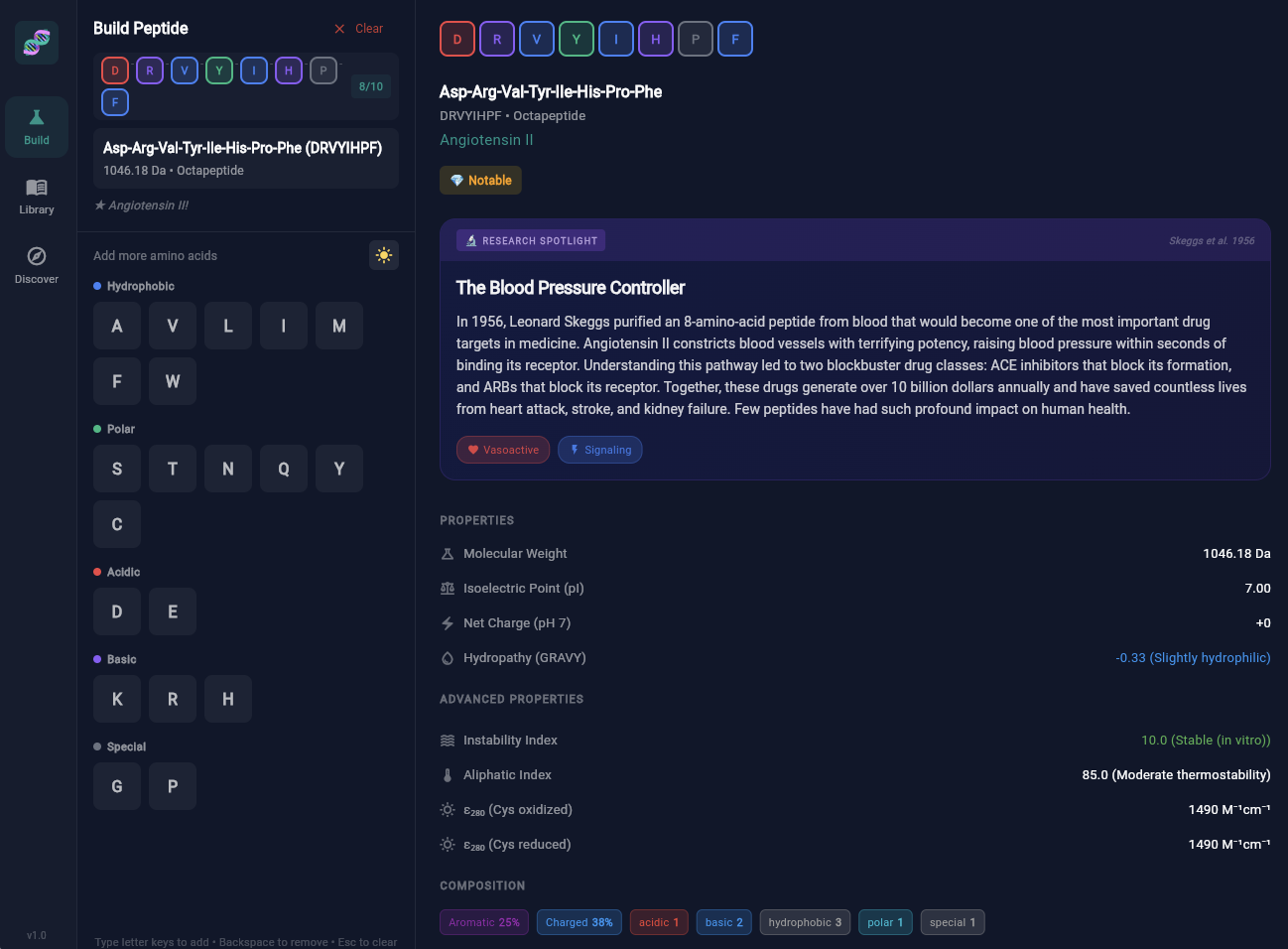

To explore that interest, I began building tools. The first was Peptide Explorer, where I treated amino acids as letters and peptides as words. The second was DNA Workbench, which approached the genome like a map you could zoom through, from genes to codons to base pairs.

What I Learned

Building forced understanding. To visualize DNA's helix, I had to learn its geometry. To calculate peptide properties, I had to implement Henderson-Hasselbalch. Every feature required research, and every bug revealed gaps in my knowledge. These projects helped me realize that bioengineering is not only about observing life, but about designing for it.

2

Why SUTD

Personal Insight Questions

"What excites you most about SUTD's approach to learning?"

What excites me most about SUTD is the way it treats learning as a process of designing, making, and iterating rather than just absorbing knowledge. I have always learned best by building things. Over the last two years I built two tools, Peptide Explorer and DNA Workbench, because I was curious about how biological information is encoded. Software became a way to explore ideas I could not access in a lab setting.

SUTD's studio culture, team-based projects, and emphasis on real-world problem framing align closely with how I already approach learning. I am motivated by creating things that help people understand the world better. SUTD is one of the few environments where that way of thinking is taken seriously and developed intentionally.

"Give an example of something you started or created. What motivated you and what did you learn from it?"

In Grade 12 I started building DNA Workbench, a web tool that lets users explore genetic sequences and mutations interactively. It began after I read about how a single base change can cause sickle cell anemia, and I wanted to visualize what that meant. Since I did not have access to a wet lab, software became my laboratory.

What motivated me was curiosity rather than a school requirement. I shared early versions with classmates and teachers and refined it based on feedback. The project taught me that building something is a different kind of understanding: trial, iteration, and fixing bugs force you to confront details that reading alone does not. It also helped me see how design can make scientific ideas more accessible.

Product Design & Engineering

Courses on how products move from concept to prototype to manufacture. I want to understand the engineering constraints that shape what designers can do.

Systems Thinking & Optimization

Courses on how complex systems work, how to model them, and how to make them better. Biology is a system. So is a city. I want to learn the shared language.

Computational & Information Systems

Courses on software architecture, data structures, and how information flows through systems. This connects directly to the tools I've been building.

Design + AI

Courses at the intersection of design thinking and machine learning. AlphaFold transformed protein prediction. I want to build tools at this frontier.

"I don't just want to study technology. I want to learn to design with it."

3

Design Project

DNA Workbench

Making the invisible visible through interactive visualization

dna.adhvai.com

The Design Problem

DNA exists at a scale beyond perception. Textbook diagrams flatten something three-dimensional into static abstraction. I wanted to see it, rotate it, explore it—and understand why a single letter change can cause disease.

The Technical Challenge

How do you create depth perception on a 2D screen without WebGL or 3D libraries? I invented a "2.5D" approach: combining opacity gradients, scale variation, and z-ordering to make the helix feel three-dimensional. 80% of the visual impact with 20% of the complexity.

Design Decision: Why Not True 3D?

WebGL would enable shadows and complex lighting—but adds dependencies, accessibility issues, and maintenance complexity. Constraints bred creativity: building depth from first principles taught me why depth cues work.

Three Depth Cues Working Together

1. Opacity Gradient

Distant objects appear hazier (atmospheric perspective). Back bases fade to 30% opacity; front bases stay fully opaque.

2. Scale Variation

Nearby objects appear larger (perspective). Front bases scale to 115%; back shrink to 85%. 30% size difference creates strong depth.

3. Z-Ordering

Closer objects overlap distant ones. The render loop sorts by depth, drawing back-to-front (painter's algorithm).

4

Design Philosophy

Progressive Disclosure Through Layers

Complex information systems fail when they present everything at once. Inspired by Google Maps' terrain/satellite/traffic toggles, I designed a layer architecture that lets users build understanding incrementally.

The 12-Layer System

Each layer represents a distinct biological concept:

Structure Layers

Ribbon Backbone · Shaped Bases · Hydrogen Bonds · 5'→3' Direction Markers

Codon Layers

Codon Color Bands · Amino Acid Labels · Wobble Position · Start/Stop Codons

Chemistry & Site Layers

GC Content · Bond Strength · Mutation Zones · Restriction Enzyme Sites

Layer Dependencies Teach Biology

Enabling "Amino Acid Labels" automatically activates "Codon Colors" because amino acids only make sense in codon context. The interface enforces biological relationships through interaction design.

Design Insight

The layer system started with 4 toggles; it grew to 12. The architecture accommodated this growth because the pattern was right from the beginning. Progressive disclosure scales.

Traditional vs. Layer Architecture

Traditional: Show everything at once → cognitive overload.

Layers: Start minimal, add on demand → scaffolded understanding. The interface guides attention rather than overwhelming it.

Mutation Stories: Where Molecules Meet Medicine

Each mutation in the database includes gene name, molecular mechanism, clinical manifestation, and a human story that makes the science memorable.

Sickle Cell (HBB)

A→T at position 17. Glutamic acid→Valine creates a hydrophobic "sticky patch." Heterozygous carriers have 40% malaria resistance.

Huntington (HTT)

CAG repeat expansion. Normal: 10-35 repeats. Disease: 40+. Repeats unstable during inheritance—genetic anticipation.

Marfan (FBN1)

Fibrillin-1 mutations weaken connective tissue. Paganini's long fingers enabled impossible violin passages.

dna.adhvai.com

5

The Craft

Iterative Development

DNA Workbench was built through hundreds of design-implement-test cycles. Each iteration brought the visualization closer to the intended educational experience.

Development Phases

1. Research & Curation

Selecting genetic diseases based on clinical significance and educational value. Verifying mechanisms against medical literature. Choosing which molecular details to visualize.

2. Architecture & Design

Evaluating rendering approaches (WebGL vs. Canvas vs. CustomPainter). Designing the layer toggle system. Creating information hierarchy from simple backbone to complex mutation data.

3. Implementation & Testing

Translating visual specifications into working code. Testing each iteration in-browser. Refining until depth perception and layer interactions felt natural.

4. Validation & Polish

Verifying scientific accuracy against primary sources. Testing across devices. Profiling performance to maintain 60fps during rotation.

What I Learned

Constraints Breed Creativity

Without a 3D library, I built depth perception from first principles. The 2.5D approach forced me to understand why depth cues work rather than just using an API.

Domain Knowledge Is Non-Negotiable

I could not design mutation narratives without understanding genetics. Surface knowledge won't create great educational tools.

SUTD Connection

I'm particularly drawn to the Healthcare specialization in EPD—where design thinking meets medical challenges. I'm also interested in robotics and computer engineering in ESD. SUTD's flexibility means I can explore before specializing.

Good Tools Emerge from Iteration, Not Inspiration

The final product reflects hundreds of small refinements: adjusting opacity curves for depth, tuning rotation speed, balancing information density on each layer. AI tools helped me iterate faster, but the vision—and the scientific curation—was mine. This is how I want to keep building: human vision + computational velocity.

35 Source Files

60 FPS Target

8 Mutation Stories

12 Visual Layers

dna.adhvai.com

6

Design Project

Peptide Explorer

Three Amino Acids. A Paradigm Shift.

In 1973, Dr. Loren Pickart discovered that a tiny tripeptide—Gly-His-Lys—could restore aged liver cells to youthful function. GHK-Cu is now in clinical trials for wound healing, skin regeneration, and COPD. It modulates over 4,000 genes.

Three letters. Copper-binding. The smallest functional unit of a much larger protein.

The Design Insight

"Amino acids are like letters, peptides are like words." I wanted to build something that made this analogy interactive—where users could chain letters and discover what words emerged.

What I Built

504 Entries

20 amino acids + 400 dipeptides + 79 notable peptides + 15 research spotlights. Organized by structure, length, and biological function.

23 Bioactivity Categories

Antimicrobial, ACE inhibitor, cell adhesion, opioid activity... Peptides organized by what they do, not just what they are.

42 3D Structures

Interactive molecular viewers integrated from PubChem. Drag to rotate, scroll to zoom, choose rendering styles.

504 Entries

42 3D Structures

23 Bioactivity Categories

PubChem Integration

7

The Craft

What Building These Tools Taught Me

Skills I Developed

Domain Knowledge Is Non-Negotiable

I could not design discovery hints without understanding which peptides matter and why. Surface knowledge won't create great educational tools. I had to learn biochemistry deeply enough to curate it for others.

Constraints Breed Creativity

With 504 entries to organize, I invented the two-tier filter system. The Discover tab emerged from the need to make bioactivities explorable. Limitations forced innovation.

AI Changes How We Build

Human vision + AI velocity. I provided scientific curation and design decisions; AI helped me iterate faster. Neither alone could have built this.

From First App to Confidence

Peptide Explorer was my first shipped product. It taught me that I can build things. That confidence carried over to DNA Workbench, to the formula apps, to everything after.

Evidence of Design Thinking

These projects weren't school assignments. They're evidence of how I think:

I See Problems as Opportunities

"I can't visualize DNA" became "I'll build a tool." This mindset—turning frustration into creation—is what SUTD cultivates.

I Learn by Making

I didn't study biochemistry to build these tools. I built these tools to learn biochemistry. The making drove the learning.

I Iterate Based on Feedback

Both projects went through multiple versions. User confusion became design revision. This is human-centered design.

I Ship Real Products

These aren't prototypes. They're live, deployed tools that people can use. I understand what it takes to finish something.

Where I Want to Go at SUTD

I'm drawn to the Healthcare specialization in EPD—medical devices, diagnostics, health interfaces. But I'm also interested in robotics and computer engineering in ESD. SUTD's flexibility means I can explore before specializing. These projects prove I can build things; SUTD will teach me what to build next.

Healthcare Design

Computer Engineering

Robotics

Systems Thinking

Human-Centered Design

peptide.adhvai.com

9

Quantitative Foundation

Mathematical & Scientific Preparation

The foundation that rigorous design requires

How Building These Apps Prepared Me

Chemistry

1,431 formulas including thermodynamics, kinetics, and organic reactions. Understanding how energy flows and molecules interact.

Physics

1,187 formulas. Fluid dynamics. Electromagnetism. Wave equations. The physical world reduced to mathematical models I can manipulate.

Mathematics

1,072 formulas with derivations. Differential equations. Linear algebra. Statistics. The language of modeling complex systems.

SUTD Connection

Design without quantitative rigor is decoration. SUTD's approach requires understanding the math behind the systems you design. Building these apps while studying for IIT-JEE gave me that foundation.

Learning by Teaching

The Formula App Approach

I didn't just compile formulas. I wrote derivations that explain why each formula works. Teaching something forces you to understand it deeply.

3,690 Formulas

Each one with context, diagrams, and practical applications. This is the kind of thorough understanding that makes quantitative work possible.

1,400+ Derivations

Not just "what" but "why." Each derivation traces the logic from first principles. This is how I think about problems.

10

Observation Skills

Seeing Structure, Recognizing Patterns

How learning to draw trained me to observe the invisible architecture in biological systems

Pattern Recognition Through Drawing

When you draw, you learn to see what others miss. A lion's mane follows a hierarchy of flow. A cathedral reveals symmetry and proportion. A face has ratios that feel "right" even before you can name them. Drawing trained me to decompose complexity into patterns.

Design Sensibility in Daily Life

This attention to form shapes how I live. I own fewer clothes and shoes, but they're designed. I notice when a chair, a typeface, or a kitchen layout is made with intention. Good design isn't decoration. It's evidence that someone understood how something would be used.

Why This Matters for Design

Design requires seeing structure at scales you can't directly observe. Protein conformations. System architectures. User mental models. The ability to recognize and represent patterns is foundational to SUTD's approach.

The Same Skill, Different Scale

DNA has structure: helix pitch, major and minor grooves. Proteins fold into patterns: alpha helices, beta sheets. The observation skills from drawing transfer directly to understanding molecular architecture.

art.adhvai.com

11

Looking Forward

Skills & Aspirations

Technical Skills (Self-Taught)

AI as Thought Partner

GitHub Copilot and AI accelerated development. Directing it required understanding the technical computing and "Bio"Allied skills below, and the process expanded that understanding significantly.

Programming

Flutter/Dart, Python, JavaScript. Cross-platform development.

Visualization

Custom rendering, 2.5D projection, Canvas APIs.

Scientific Databases

PubChem, ClinVar, OMIM integration.

Web Infrastructure

Firebase, APIs, responsive design.

Domain Knowledge (Self-Taught)

Molecular Biology

DNA structure, genetic code, mutations, base pairing. I learned all of this building DNA Workbench.

Biochemistry

Amino acids, peptide bonds, Henderson-Hasselbalch, hydropathy. I learned all of this building Peptide Explorer.

What I Want to Learn at SUTD

Design Process Skills

I have built the computational foundation. Now I want to learn how to take ideas from iteration to prototype to impact, in a studio environment with team-based projects.

Design + AI

The DAI pillar combines design thinking with AI and machine learning. AlphaFold transformed protein prediction. I want to build and apply these tools at the intersection of design and computation.

Project Aspirations

I hope to work on team projects where computational models meet real-world problem framing. I want to learn from designers who think in systems.

"I have learned to build tools to explore life at the molecular level. At SUTD, I want to learn to design with intention."

Explore My Work

Adhvai Deepak Menon

Application for Design and Artificial Intelligence @ SUTD

12